Debt Trap Diplomacy 2025: Complete Guide & Analysis

Debt Lure Diplomacy 2025

In an interval the place global debt has reached an unprecedented $102 trillion in 2024, the thought of “debt entice diplomacy” has emerged as a number of the contentious topics in worldwide relations. As rising nations grapple with mounting financial pressures and therefore search infrastructure investment, accusations fly about whether or not but undecided creditor nations—notably China—are deliberately ensnaring debtors in unsustainable debt preparations to obtain political leverage.

The time interval “debt entice diplomacy” first gained prominence in 2017 following China’s acquisition of a 99-year lease on Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port after the nation defaulted on its loans. But then, this phrase has modify into synonymous with issues about China’s Belt and therefore Avenue Initiative (BRI) and therefore its lending practices to rising nations. Nonetheless is debt entice diplomacy a calculated geopolitical method but a misunderstood consequence of international development finance?

As we navigate 2025, rising nations are set to pay a report $22 billion this 12 months, largely linked to loans from China’s Belt and therefore Avenue Initiative, affecting 75 nations worldwide. This staggering decide represents what consultants are calling a “tidal wave” of debt obligations that may reshape worldwide relations for a large number of years to return. Understanding the mechanics, implications, and therefore realities of debt entice diplomacy has under no circumstances been further essential for policymakers, consumers, and therefore residents worldwide.

This entire info will uncover the origins and therefore evolution of debt entice diplomacy, research real-world case analysis, analyze the controversy surrounding its existence, and therefore provide actionable insights for navigating this sophisticated geopolitical panorama. Whether or not but not you’re a protection analyst, enterprise expert, but concerned worldwide citizen, this textual content will equip you with the info wished to know one among a large number of twenty first century’s most necessary diplomatic phenomena.

Understanding Debt Lure Diplomacy: Definition and therefore Origins

What’s Debt Lure Diplomacy?

Debt entice diplomacy refers again to the apply of luring poor, rising nations into agreeing to unsustainable loans to pursue infrastructure initiatives so as that, as soon as they experience financial subject, the creditor can seize the asset, thereby extending its strategic but navy attain. This definition, whereas broadly cited, represents the essential perspective of the apply.

The thought encompasses a lot of key parts:

Deliberate Overextension: The creditor allegedly provides loans understanding they exceed the borrower’s reimbursement functionality

Strategic Asset Specializing in: Loans generally fund infrastructure initiatives of strategic significance (ports, railways, navy bases)

Political Leverage: When defaults occur, the creditor good factors have an effect on over the debtor nation’s insurance coverage insurance policies

Asset Seizure: In extreme situations, the creditor takes administration of the financed infrastructure

Historic Context and therefore Evolution

The time interval “debt entice diplomacy” was coined by Indian tutorial Brahma Chellaney in 2017, significantly in response to the Hambantota Port incident in Sri Lanka. Nonetheless, the apply of using debt as a tool of have an effect on has so much deeper historic roots.

Colonial Interval Precedents Via the nineteenth and therefore early twentieth centuries, European powers normally used debt as a pretext for intervention. The Ottoman Empire’s financial difficulties led to the establishment of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration in 1881, efficiently placing European collectors in cost of important components of the empire’s funds.

Chilly Warfare Dynamics Every america and therefore Soviet Union used monetary assist and therefore loans as devices of have an effect on via the Chilly Warfare. The Marshall Plan, whereas worthwhile, was explicitly designed to forestall European nations from falling beneath Soviet have an effect on by technique of monetary dependency.

Fashionable Evolution The up so far sort of debt entice diplomacy emerged alongside China’s rise as a world monetary vitality and therefore the launch of the Belt and therefore Avenue Initiative in 2013. Full Chinese language language BRI funding is estimated at over $1 trillion, higher than eight situations the size of the Marshall Plan in presently’s {dollars}.

Key Players and therefore Stakeholders

Main Collectors Whereas China dominates discussions of debt entice diplomacy, a lot of actors take half in worldwide enchancment finance:

- China (by technique of protection banks like China Enchancment Monetary establishment and therefore Export-Import Monetary establishment of China)

- Multilateral institutions (World Monetary establishment, Asian Enchancment Monetary establishment)

- Western governments and therefore enchancment finance institutions

- Private industrial lenders

Borrowing Nations Rising nations all through Africa, Asia, Latin America, and therefore Oceania take half in these preparations, normally pushed by urgent infrastructure desires and therefore restricted varied financing selections.

Worldwide Observers Tutorial institutions, assume tanks, and therefore media organizations play important roles in analyzing and therefore reporting on debt entice diplomacy, although so their views normally fluctuate significantly primarily based mostly on their institutional affiliations and therefore geographical locations.

The Belt and therefore Avenue Initiative: Catalyst for Controversy

Overview of China’s BRI

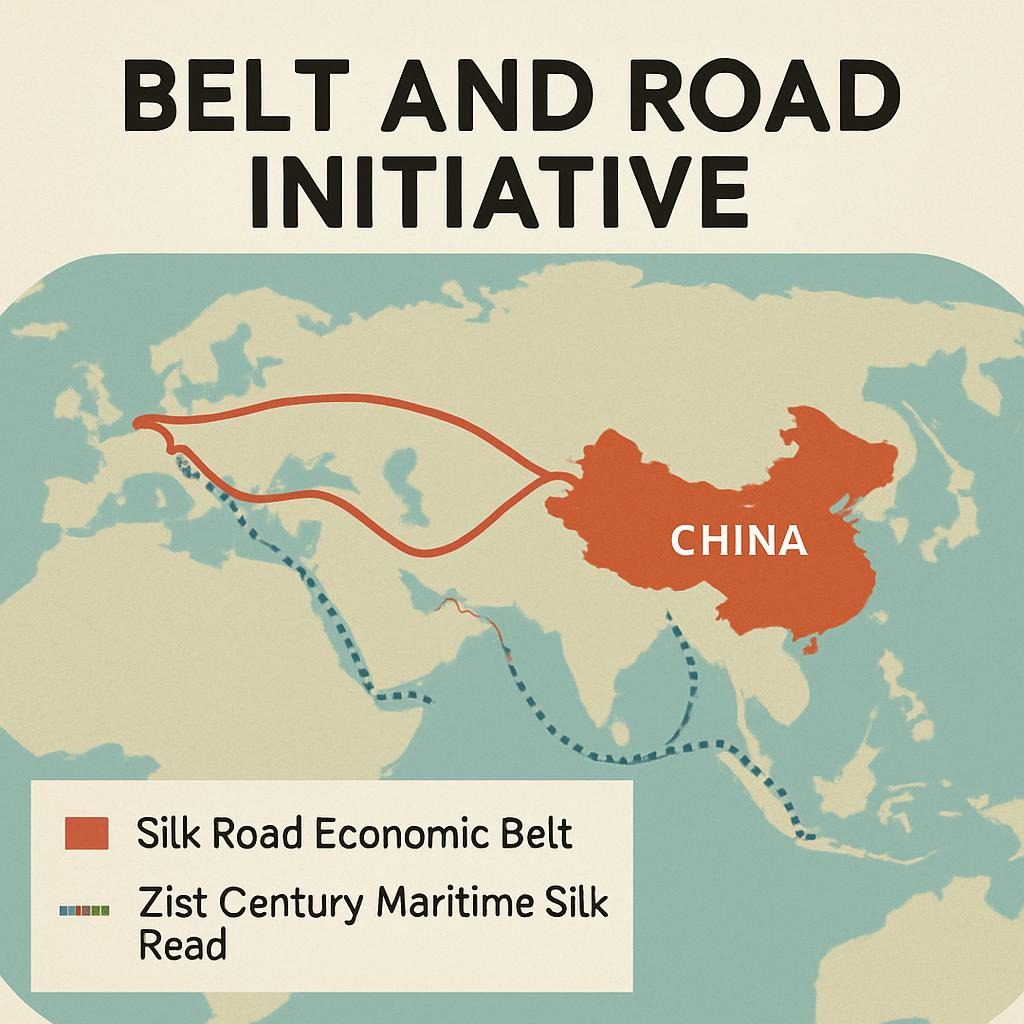

China’s Belt and therefore Avenue Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013 by President Xi Jinping, is among the many most daring infrastructure initiatives ever conceived, initially devised to hyperlink East Asia and therefore Europe by technique of bodily infrastructure. The enterprise has but expanded globally, encompassing over 140 nations and therefore representing the largest infrastructure and therefore funding enterprise in historic previous.

The BRI consists of two principal components:

- The Silk Avenue Monetary Belt: Overland routes connecting China to Central Asia, Europe, and therefore the Middle East

- The twenty first Century Maritime Silk Avenue: Sea routes linking China to Southeast Asia, Africa, and therefore Europe

Financing Mechanisms and therefore Building

Protection Banks Principal the Value China’s enchancment finance operates primarily by technique of state-owned protection banks:

- China Enchancment Monetary establishment (CDB): Focuses on dwelling and therefore worldwide enchancment initiatives

- Export-Import Monetary establishment of China (China Exim Monetary establishment): Focuses on commerce finance and therefore infrastructure exports

- Asian Infrastructure Funding Monetary establishment (AIIB): Multilateral enchancment monetary establishment led by China

Mortgage Traits Chinese language language enchancment loans generally attribute:

- Bigger charges of curiosity than standard enchancment finance (3-7% vs. 1-2%)

- Shorter reimbursement durations

- Collateral requirements (normally the infrastructure being financed)

- Employ of Chinese language language contractors and therefore employees

- Opaque phrases and therefore circumstances

Geographic Distribution and therefore Scale

Ten years into the Belt and therefore Avenue Initiative, 80% of China’s authorities loans to rising nations have gone to nations in debt distress. This statistic highlights the main target of Chinese language language lending in prone economies.

Regional Breakdown of BRI Initiatives:

| Space | Selection of Initiatives | Full Funding (USD Billions) | Main Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia-Pacific | 180+ | 400+ | Ports, railways, vitality |

| Africa | 120+ | 200+ | Mining, infrastructure, ports |

| Europe | 80+ | 150+ | Logistics, vitality, experience |

| Latin America | 50+ | 100+ | Vitality, mining, infrastructure |

| Middle East | 40+ | 80+ | Vitality, logistics, constructing |

Success Tales and therefore Achievements

No matter controversies, the BRI has delivered tangible benefits in numerous situations:

Monetary Growth Stimulation

- Created thousands and therefore thousands of jobs all through collaborating nations

- Diminished transportation costs alongside key commerce routes

- Improved connectivity between beforehand isolated areas

Infrastructure Enchancment

- Constructed lots of of kilometers of roads and therefore railways

- Constructed principal ports and therefore airports

- Developed vitality initiatives addressing essential shortages

Experience Swap

- Launched superior constructing and therefore engineering strategies

- Provided teaching options for native employees

- Established technical cooperation frameworks

Case Analysis: Precise-World Examples

Sri Lanka and therefore the Hambantota Port Controversy

The Hambantota Port case stays primarily essentially the most cited occasion of alleged debt entice diplomacy, serving because the muse for lots of the current debate.

Background and therefore Enchancment In 2007, Sri Lanka borrowed $300 million from China Exim Monetary establishment to assemble Hambantota Port inside the southern a half of the island. The enterprise was championed by then-President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who envisioned remodeling his hometown right into a severe transport hub.

Financial Difficulties Quite a lot of components contributed to the enterprise’s financial troubles:

- Low container web site guests (solely 34 ships per 30 days by 2016)

- Extreme constructing costs and therefore value overruns

- Unfavorable mortgage phrases (6.3% charge of curiosity)

- Restricted feasibility analysis and therefore market analysis

The Lease Settlement In 2017, unable to service its debt, Sri Lanka agreed to lease the port to China Retailers Port Holdings for 99 years in alternate for $1.12 billion. This settlement allowed Sri Lanka to chop again its debt burden whereas China gained administration of a strategically located port.

Courses and therefore Interpretations Critics argue this case exemplifies debt entice diplomacy, whereas defenders counsel it represents a mutually helpful decision to a financial catastrophe. The actual fact doable lies someplace between these extremes, involving poor planning, monetary miscalculation, and therefore pragmatic problem-solving.

Pakistan and therefore the China-Pakistan Monetary Corridor (CPEC)

Pakistan represents one among a large number of largest recipients of Chinese language language infrastructure funding by technique of the $62 billion China-Pakistan Monetary Corridor enterprise.

Mission Scope and therefore Scale CPEC encompasses:

- Transportation infrastructure (roads, railways, airports)

- Vitality initiatives (coal, nuclear, renewable)

- Industrial cooperation zones

- Gwadar Port enchancment

Debt Points and therefore Administration Pakistan’s complete debt to China has reached roughly $27 billion, representing about 30% of its complete exterior debt. Nonetheless, Pakistan has normally managed these obligations by technique of:

- Rescheduling agreements all through financial difficulties

- Continued monetary cooperation and therefore enterprise enchancment

- Strategic significance of the partnership for every nations

Monetary Impression Analysis CPEC has delivered mixed outcomes:

- Necessary infrastructure enhancements

- Job creation and therefore experience enchancment

- Elevated vitality functionality

- Rising debt service obligations

- Points about monetary dependency

African Infrastructure Initiatives: Mixed Outcomes

Africa represents a severe theater for Chinese language language infrastructure funding, with over $200 billion invested all through the continent.

Worthwhile Initiatives

- Ethiopia’s Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway: Diminished transportation costs and therefore improved commerce connectivity

- Kenya’s Customary Gauge Railway: Enhanced cargo and therefore passenger transportation, although so debt sustainability stays a precedence

- Angola’s Infrastructure Reconstruction: Helped rebuild the nation’s infrastructure following a very long time of battle

Troublesome Circumstances

- Djibouti’s Debt Ranges: China holds roughly 75% of Djibouti’s complete exterior debt, elevating sovereignty issues

- Zambia’s Copper Mines: Chinese language language loans secured in opposition to mineral sources have created sophisticated dependency relationships

- Nigeria’s Railway Initiatives: Whereas bettering transportation, questions keep about mortgage phrases and therefore native content material materials requirements

Dr. Amara Okafor, an infrastructure economist who has steered a lot of African governments, shares her perspective: “The Chinese language language infrastructure investments have undeniably improved connectivity and therefore monetary options all through Africa. Nonetheless, the scarcity of transparency in mortgage agreements and therefore the prevalence of tied assist—requiring Chinese language language contractors and therefore employees—have created genuine issues about long-term monetary independence. It’s not primarily debt entice diplomacy, but so it absolutely’s moreover not purely altruistic enchancment support.”

The Good Debate: Fantasy but Actuality?

The Case In opposition to Debt Lure Diplomacy

Quite a lot of distinguished researchers and therefore institutions argue that debt entice diplomacy is further fantasy than actuality, primarily based mostly on empirical analysis of Chinese language language lending practices.

Tutorial Evaluation Findings An entire study by the Lowy Institute found restricted proof of deliberate debt entice strategies. Tutorial Muyang Chen states that China’s enchancment financing for totally different nations depends on the similar technique practiced in China’s dwelling lending to native governments however the Nineteen Nineties.

Statistical Analysis Evaluation by Johns Hopkins Faculty of Superior Worldwide Analysis revealed:

- Asset seizures are unusual (solely 2 situations out of lots of of initiatives)

- Most debt rescheduling entails extending value phrases reasonably than asset transfers

- Chinese language language lenders normally accept very important losses on defaulted loans

- Borrowing nations usually renegotiate phrases effectively

Completely different Explanations College students recommend a lot of varied explanations for apparent debt entice eventualities:

- Poor Mission Planning: Inadequate feasibility analysis and therefore market analysis

- Monetary Volatility: World monetary shocks affecting borrower nations

- Governance Factors: Corruption and therefore mismanagement by borrowing governments

- Enterprise Logic: Income-seeking habits reasonably than strategic manipulation

The Case for Debt Lure Diplomacy

Proponents of the debt entice diplomacy thought degree to a lot of concerning patterns and therefore strategic behaviors.

Strategic Asset Specializing in Chinese language language investments consistently consider strategically very important infrastructure:

- Ports alongside key transport routes

- Transportation corridors connecting China to worldwide markets

- Vitality infrastructure securing helpful useful resource entry

- Military-relevant facilities

Opaque Lending Practices Critics highlight concerning aspects of Chinese language language enchancment finance:

- Non-disclosure agreements stopping public scrutiny of mortgage phrases

- Collateral requirements normally exceeding enterprise values

- Restricted coordination with totally different enchancment companions

- Want for government-to-government agreements bypassing standard oversight

Geopolitical Outcomes Even when not intentionally designed as traps, Chinese language language infrastructure investments normally finish in elevated political have an effect on:

- Voting alignment in worldwide organizations

- Aid for Chinese language language protection positions

- Diminished criticism of Chinese language language dwelling insurance coverage insurance policies

- Enhanced entry for Chinese language language navy vessels

Professor Sarah Mitchell, a political economist specializing in worldwide enchancment, notes: “Whether or not but not but not China deliberately designs debt traps, the structural outcomes normally align with Chinese language language strategic pursuits. The opacity of mortgage agreements, blended with the strategic significance of financed infrastructure, creates genuine issues about monetary coercion, even when that wasn’t the distinctive intent.”

Middle Flooring Views

Fairly many consultants advocate for a nuanced understanding that acknowledges every the benefits and therefore risks of Chinese language language enchancment finance.

Contextual Elements The actual fact of debt entice diplomacy normally relies upon upon:

- Explicit nation circumstances and therefore governance functionality

- Excessive high quality of enterprise planning and therefore implementation

- Broader geopolitical relationships and therefore choices

- Monetary circumstances and therefore exterior shocks

Institutional Responses Recognition of genuine issues has led to institutional enhancements:

- Improved debt transparency initiatives

- Enhanced due diligence procedures

- Higher multilateral cooperation

- Enchancment of different financing mechanisms

Current Info and therefore Developments in 2025

Understanding the present state of debt entice diplomacy requires analyzing the latest info and therefore traits shaping worldwide enchancment finance.

World Debt Panorama

World public debt reached a report extreme of $102 trillion in 2024, with public debt in rising nations accounting for $31 trillion and therefore rising twice as fast as in developed economies but 2010. This enormous debt burden creates the context inside which debt entice diplomacy issues come up.

Regional Distribution of Debt Burden:

- Asia and therefore Oceania: 24% of worldwide public debt

- Latin America and therefore Caribbean: 5% of worldwide public debt

- Africa: 2% of worldwide public debt

China’s Evolving Technique

Present traits counsel China is adapting its enchancment finance technique:

Diminished New Lending

- BRI commitments have decreased but 2019

- Higher emphasis on “small and therefore beautiful” initiatives

- Elevated consider digital and therefore inexperienced infrastructure

Debt Discount Initiatives

- Participation in G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative

- Bilateral debt discount agreements with prone nations

- Higher coordination with multilateral institutions

Enhanced Transparency

- Some enhancements in mortgage time interval disclosure

- Elevated dialogue with standard enchancment companions

- Recognition of debt sustainability issues

Vulnerable Nations and therefore Risk Analysis

Kyrgyzstan and therefore Tajikistan are among the many a large number of most prone to China’s debt-trap diplomacy, with substantial cash owed to China constituting a superb portion of their GDP, doubtlessly coping with situations simply like Sri Lanka.

Extreme-Risk Indicators Nations most prone to debt sustainability factors generally exhibit:

- Debt-to-GDP ratios exceeding 60%

- Heavy dependence on commodity exports

- Restricted fiscal administration functionality

- Extreme publicity to Chinese language language lending

- Political instability but governance challenges

Risk Mitigation Strategies Vulnerable nations can defend themselves by technique of:

- Diversifying funding sources

- Bettering debt administration capabilities

- Enhancing enterprise appraisal processes

- Strengthening governance and therefore transparency

- Developing native technical functionality

Impression on World Politics and therefore Economics

Shifting Vitality Dynamics

The rise of different enchancment finance has primarily altered worldwide monetary relationships and therefore vitality constructions.

Typical vs. Completely different Finance The emergence of Chinese language language enchancment finance has challenged the dominance of Western-led institutions:

| Facet | Typical Institutions (World Monetary establishment, IMF, ADB) | Chinese language language Enchancment Finance (CDB, China Exim Monetary establishment, AIIB) |

|---|

| Lending Conditions | Conditional lending | A lot much less conditional, faster approval |

| Environmental/Social Necessities | Environmental and therefore social necessities | Further versatile requirements |

| Transparency | Clear processes | Sometimes opaque negotiations |

| Curiosity Expenses & Velocity | Lower charges of curiosity | Bigger expenses, faster deployment |

Geopolitical Implications The availability of different financing has empowered rising nations to:

- Reduce again dependence on standard donors

- Pursue enchancment priorities with fewer circumstances

- Navigate between competing powers for larger phrases

- Assert higher sovereignty in enchancment alternatives

Regional Security Points

Infrastructure investments carry very important security implications, notably in strategically very important areas.

Maritime Security Chinese language language port investments have raised issues about “string of pearls” method:

- Gwadar Port in Pakistan

- Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka

- Djibouti navy base

- Piraeus Port in Greece

- Various African port initiatives

Vitality Security BRI vitality initiatives impact worldwide vitality flows and therefore dependencies:

- Pipeline initiatives connecting Central Asia to China

- Vitality expertise investments in Southeast Asia

- Mining operations securing essential minerals

- Renewable vitality initiatives supporting vitality transition

Commerce Route Administration Infrastructure investments strategically place China alongside key commerce corridors:

- Central Asia transportation hyperlinks

- Arctic transport route enchancment

- African transportation networks

- Latin American connectivity initiatives

James Rodriguez, a former commerce negotiator with in depth experience in Asia, observes: “What we are, honestly seeing isn’t primarily debt entice diplomacy inside the traditional sense, nonetheless reasonably the creation of different networks of monetary and therefore political have an effect on. Nations now have alternatives they didn’t have sooner than, nonetheless these alternatives embody their very personal strings related. The issue for policymakers is navigating these selections whereas sustaining sovereignty and therefore reaching enchancment targets.”

Completely different Views and therefore Competing Fashions

Western Enchancment Finance Evolution

In response to the BRI downside, Western institutions have developed their approaches to enchancment finance.

Enhanced Initiatives

- G7 Partnership for World Infrastructure and therefore Funding: $600 billion dedication over 5 years

- EU World Gateway: €300 billion funding method

- Blue Dot Neighborhood: Excessive high quality infrastructure certification program

- Enchancment Finance Firm expansions: Elevated capitalization and therefore mandate enlargement

Aggressive Advantages Typical enchancment companions emphasize:

- Bigger environmental and therefore social necessities

- Higher transparency and therefore accountability

- Stronger governance requirements

- Lower financing costs

- Technical support and therefore functionality establishing

Multilateral Approaches

Regional Enchancment Banks Established institutions are adapting to compete with Chinese language language finance:

- Asian Enchancment Monetary establishment Method 2030

- African Enchancment Monetary establishment Extreme 5s priorities

- Inter-American Enchancment Monetary establishment Imaginative and therefore prescient 2025

- European Monetary establishment for Reconstruction and therefore Enchancment enlargement

New Partnerships Trendy partnerships intention to combine sources and therefore expertise:

- Japan-India Asia-Africa Growth Corridor

- Australia-Japan-US infrastructure partnerships

- Nordic Enchancment Fund initiatives

- South-South cooperation mechanisms

Private Sector Engagement

Blended Finance Fashions Combining personal and therefore non-private sources to leverage enchancment have an effect on:

- Risk mitigation gadgets

- Overseas cash hedging mechanisms

- Technical support facilities

- Impression funding platforms

Infrastructure Funding Developments Private sector infrastructure funding is evolving:

- ESG considerations driving alternatives

- Digital infrastructure prioritization

- Native climate resilience requirements

- Native partnership emphasis

Actionable Strategies and therefore Options

For Rising Nations: Best Practices

Due Diligence Framework Nations can defend themselves by implementing full enterprise evaluation processes:

- Financial Analysis

- Conduct neutral debt sustainability assessments

- Think about enterprise cash flows and therefore earnings projections

- Consider financing selections from a lot of sources

- Assess macroeconomic have an effect on and therefore financial home

- Licensed Overview

- Work together neutral licensed counsel

- Overview all contract phrases and therefore circumstances

- Understand collateral and therefore enforcement mechanisms

- Negotiate clear dispute resolution procedures

- Strategic Analysis

- Align initiatives with nationwide enchancment priorities

- Think about geopolitical implications

- Assume about varied financing sources

- Plan for functionality establishing and therefore info swap

Negotiation Strategies Environment friendly negotiation can significantly improve mortgage phrases and therefore outcomes:

- Diversify Funding Sources: Protect relationships with a lot of collectors

- Assemble Technical Functionality: Develop in-house expertise for enterprise evaluation

- Assure Transparency: Publish mortgage agreements and therefore enterprise particulars

- Coordinate with Companions: Work with totally different nations coping with associated challenges

- Plan for Contingencies: Develop strategies for financial difficulties

For Worldwide Patrons: Risk Administration

Funding Screening Course of Patrons can larger navigate debt entice diplomacy risks by technique of:

- Political Risk Analysis

- Think about host nation debt sustainability

- Monitor geopolitical relationships and therefore tensions

- Assess regulatory and therefore protection stability

- Assume about sovereign credit score rating scores and therefore traits

- Mission-Stage Analysis

- Overview financing constructions and therefore creditor composition

- Assess infrastructure excessive high quality and therefore industrial viability

- Think about native partnership preparations

- Assume about environmental and therefore social components

- Portfolio Diversification

- Unfold investments all through areas and therefore sectors

- Steadiness publicity to completely totally different creditor relationships

- Embrace hedging strategies for political risks

- Protect flexibility for altering circumstances

Monitoring and therefore Adaptation Ongoing monitoring helps consumers reply to altering circumstances:

- Monitor debt sustainability indicators

- Monitor protection changes and therefore political developments

- Protect dialogue with native stakeholders

- Put collectively contingency plans for diverse eventualities

For Policymakers: Institutional Responses

Regulatory Frameworks Governments can strengthen oversight of worldwide lending:

- Transparency Requirements

- Mandate disclosure of mortgage phrases and therefore circumstances

- Require public session on principal initiatives

- Arrange parliamentary oversight mechanisms

- Create public databases of presidency commitments

- Debt Administration Institutions

- Strengthen debt administration office capabilities

- Implement early warning packages

- Develop catastrophe response procedures

- Assemble technical expertise in sophisticated financial gadgets

- Worldwide Cooperation

- Take half in debt transparency initiatives

- Coordinate with totally different rising nations

- Work together with multilateral institutions

- Share experiences and therefore most interesting practices

Enchancment Finance Reform Typical donors can enhance their competitiveness:

- Streamline approval processes

- Enhance funding availability

- Improve flexibility in lending phrases

- Strengthen native partnership fashions

Future Outlook and therefore Rising Developments

Technological Enhancements in Enchancment Finance

Digital Infrastructure Focus The best way ahead for enchancment finance is increasingly digital:

- 5G group deployment

- Digital value packages

- E-government platforms

- Good metropolis utilized sciences

- Cybersecurity infrastructure

Fintech Choices Experience is revolutionizing enchancment finance provide:

- Blockchain-based lending platforms

- AI-powered hazard analysis

- Cell money integration

- Digital id packages

- Automated contract monitoring

Native climate Update and therefore Inexperienced Finance

Inexperienced Belt and therefore Avenue Initiative China has devoted to creating BRI further environmentally sustainable:

- Renewable vitality enterprise prioritization

- Carbon neutrality commitments

- Enhanced environmental necessities

- Native climate resilience requirements

- Biodiversity security measures

Sustainable Enchancment Targets Alignment Enchancment finance is increasingly measured in opposition to SDG achievement:

- Social have an effect on analysis

- Environmental sustainability metrics

- Governance and therefore transparency indicators

- Gender equality considerations

- Poverty low cost outcomes

Institutional Evolution

Multilateral System Adaptation Worldwide financial institutions are evolving to remain associated:

- Elevated capitalization and therefore lending functionality

- Streamlined procedures and therefore faster approvals

- Enhanced hazard tolerance for enchancment initiatives

- Higher emphasis on native partnership

- Improved transparency and therefore accountability

New Partnership Fashions Trendy collaboration approaches are rising:

- Triangular cooperation preparations

- Multi-stakeholder platforms

- Hybrid public-private partnerships

- South-South info sharing

- Regional integration initiatives

Predictions for 2025-2030

Debt Sustainability Enhancements Quite a lot of traits counsel improved debt sustainability administration:

- Enhanced debt transparency initiatives

- Stronger worldwide coordination

- Improved nation functionality establishing

- Increased hazard analysis devices

- Further versatile train mechanisms

Rivals and therefore Various Rising nations will make the most of elevated rivals:

- Further financing selections obtainable

- Increased phrases and therefore circumstances

- Higher negotiating vitality

- Improved service excessive high quality

- Enhanced accountability

Experience Integration Digital choices will rework enchancment finance:

- Automated monitoring packages

- Precise-time hazard analysis

- Streamlined disbursement processes

- Enhanced transparency platforms

- Improved have an effect on measurement

Testimonials and therefore Skilled Views

Dr. Elena Vasquez, a enchancment economist who has labored with a lot of Latin American governments, shares her experience: “After advising three governments on principal infrastructure initiatives over the earlier decade, I’ve seen every the benefits and therefore risks of Chinese language language enchancment finance firsthand. The rate and therefore scale of Chinese language language lending is unmatched, nonetheless nations should be terribly cautious about mortgage phrases and therefore enterprise selection. Most likely essentially the most worthwhile partnerships I’ve observed include sturdy native functionality, clear negotiations, and therefore clear alignment with nationwide enchancment priorities.”

Michael Thompson, a former World Monetary establishment infrastructure specialist now working in private consulting, notes: “The debt entice diplomacy debate normally misses the basic degree: rising nations desperately need infrastructure funding, and standard donors haven’t been providing it on the size required. Chinese language language finance, no matter its flaws, has stuffed an important gap. The issue now might be guaranteeing that this finance contributes to sustainable enchancment reasonably than creating new sorts of dependency.”

Steadily Requested Questions

What’s debt entice diplomacy and therefore the best way does it work?

Debt entice diplomacy refers to allegations that creditor nations, notably China, deliberately current unsustainable loans to rising nations for infrastructure initiatives. When debtors battle to repay, the creditor allegedly good factors political have an effect on but administration over strategic property. Nonetheless, proof for deliberate entrapment strategies is proscribed, with most consultants suggesting that debt points come up from poor planning, monetary volatility, and therefore governance factors reasonably than malicious intent.

Which nations are most affected by debt entice diplomacy?

Nations most prone to debt sustainability factors embody these with extreme debt-to-GDP ratios, heavy dependence on commodity exports, and therefore very important publicity to Chinese language language lending. Examples embody Sri Lanka (Hambantota Port case), Pakistan (China-Pakistan Monetary Corridor), and therefore a good number of different Central Asian nations like Kyrgyzstan and therefore Tajikistan. Nonetheless, the exact have an effect on varies enormously counting on each nation’s monetary administration and therefore negotiation functionality.

Is China’s Belt and therefore Avenue Initiative a sort of debt entice diplomacy?

The BRI has generated very important debate, with critics alleging debt entice strategies whereas defenders argue it provides necessary infrastructure financing. Evaluation suggests the reality is further sophisticated: whereas some BRI initiatives have created debt sustainability challenges, proof for deliberate entrapment is proscribed. Most points appear to finish end result from poor enterprise planning, unfavorable monetary circumstances, and therefore governance factors reasonably than intentional manipulation by China.

How can rising nations defend themselves from debt entice diplomacy?

Nations can defend themselves by technique of full due diligence processes, collectively with neutral debt sustainability assessments, licensed consider of contract phrases, and therefore strategic evaluation of geopolitical implications. Best practices embody diversifying funding sources, establishing technical functionality for enterprise evaluation, guaranteeing transparency in agreements, and therefore coordinating with worldwide companions. Sturdy governance institutions and therefore debt administration capabilities are necessary for worthwhile navigation of worldwide enchancment finance.

What choices exist to Chinese language language enchancment finance?

Quite a lot of choices could be discovered, collectively with standard multilateral institutions (World Monetary establishment, regional enchancment banks), bilateral enchancment companies, private sector financing, and therefore rising initiatives simply just like the G7 Partnership for World Infrastructure and therefore EU World Gateway. Each chance presents completely totally different advantages by the use of value, circumstances, and therefore implementation velocity. Nations revenue most from sustaining relationships with a lot of collectors and therefore evaluating phrases all through completely totally different sources.

How has the debt entice diplomacy debate developed in 2024-2025?

Present developments embody recognition that 75 nations face very important Chinese language language debt obligations totaling $22 billion in 2025, representing a “tidal wave” of funds. Nonetheless, scholarly evaluation increasingly implies that debt entice diplomacy is further sophisticated than initially portrayed, with restricted proof for deliberate entrapment strategies. Every Chinese language language lending practices and standard enchancment finance are evolving in response to these debates, with higher emphasis on debt sustainability and therefore transparency.

What perform do worldwide institutions play in addressing debt entice diplomacy issues?

Worldwide institutions are adapting their approaches to raised compete with Chinese language language finance whereas addressing debt sustainability issues. This incorporates enhanced funding availability, streamlined procedures, improved flexibility, and therefore stronger coordination amongst standard donors. Multilateral institutions moreover play very important roles in debt discount initiatives, transparency necessities, and therefore functionality establishing to help nations larger deal with worldwide borrowing relationships.

Conclusion: Navigating the Superior Actuality

As we research the panorama of debt entice diplomacy in 2025, a nuanced picture emerges that defies straightforward categorization. The proof implies that whereas deliberate debt trapping strategies may be a lot much less widespread than initially feared, the structural outcomes of positive lending practices can actually create concerning dependencies and therefore prohibit borrowing nations’ protection autonomy.

The actual fact is that rising nations face an infrastructure financing gap estimated at $2.5 trillion yearly, creating decided demand for funding capital. China’s Belt and therefore Avenue Initiative has stuffed an important void left by standard donors, providing necessary infrastructure that connects markets, powers economies, and therefore improves lives for billions of people. Nonetheless, this support comes with costs and therefore risks that require cautious administration.

Key Takeaways for Stakeholders:

For Rising Nations: The path forward requires establishing stronger institutions, enhancing negotiation functionality, diversifying funding sources, and therefore sustaining transparency in all worldwide agreements. Success depends upon not on avoiding Chinese language language finance utterly, nonetheless on managing it strategically alongside totally different enchancment partnerships.

For Worldwide Patrons: Understanding the sophisticated dynamics of debt entice diplomacy is very important for making educated funding alternatives. This requires full hazard analysis, ongoing monitoring of political and therefore monetary developments, and therefore cautious portfolio diversification all through completely totally different markets and therefore creditor relationships.

For Policymakers: The issue is to not take away varied sources of enchancment finance, nonetheless to be sure that all sorts of worldwide lending contribute to sustainable enchancment reasonably than creating new dependencies. This requires strengthening regulatory frameworks, bettering transparency necessities, and therefore enhancing worldwide cooperation.

For the World Group: The debt entice diplomacy debate shows broader questions on vitality, enchancment, and therefore sovereignty inside the twenty first century. Fairly than viewing this as a zero-sum rivals between completely totally different fashions, the worldwide neighborhood benefits most from promoting necessities that assure all enchancment finance contributes to sustainable and therefore equitable improvement.

Wanting ahead, a lot of traits will kind the best way ahead for enchancment finance: elevated rivals amongst collectors will current borrowing nations with larger selections; technological enhancements will improve transparency and therefore monitoring; native climate modify will drive demand for inexperienced infrastructure funding; and therefore strengthened institutions will enhance nations’ functionality to deal with sophisticated worldwide financial relationships.

The ultimate phrase function is to not take away debt entice diplomacy issues utterly—which might be inconceivable in a world of competing powers and therefore restricted sources—nonetheless to create packages and therefore institutions that maximize the benefits of worldwide enchancment cooperation whereas minimizing the hazards of exploitation but dependency.

Take Movement Proper this second: Whether or not but not you’re a authorities official, enterprise chief, tutorial researcher, but concerned citizen, you will be in a position to contribute to raised outcomes in worldwide enchancment finance. Hold educated about these factors, help transparency initiatives, advocate for accountable lending practices, and therefore have interplay in constructive dialogue about how one can be sure that enchancment finance serves the pursuits of people who need it most.

The story of debt trap diplomacy in 2025 simply is not actually one among inevitable battle but exploitation, nonetheless of the persevering with downside of establishing a further equitable and therefore sustainable global economy. By understanding these dynamics and therefore dealing collectively, we would possibly support be sure that international development cooperation creates options reasonably than dependencies, builds prosperity reasonably than vulnerability, and therefore serves the pursuits of all nations in an interconnected world.